The photograph should have been unremarkable.

That was the unsettling part.

Dr. Maya Freeman had handled thousands like it during her years at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture—sepia portraits, formal poses, stiff expressions held through long exposures.

Families documented for reasons no archive could fully explain: proof of existence, dignity preserved on fragile paper.

This one, cataloged simply as Unknown Black Family, Mississippi, circa nineteen hundred, had spent decades untouched in a climate-controlled drawer, quietly aging while the world forgot it.

Until March of twenty twenty-four.

Maya slid the photograph from its archival sleeve beneath the examination light, adjusting her magnifier out of habit more than curiosity.

The image was unusually well preserved.

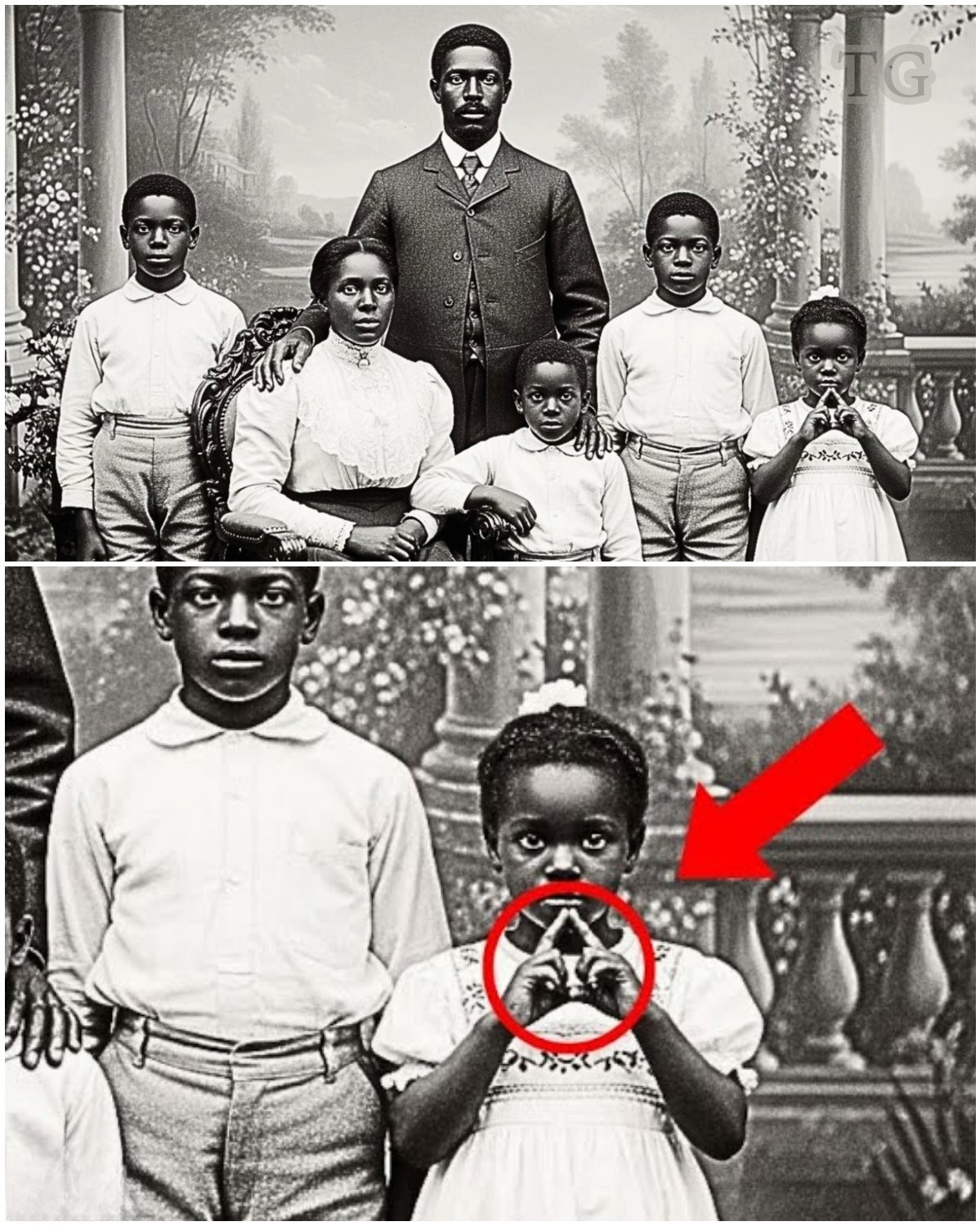

Six figures stared back at her: a father standing, hand resting protectively on his wife’s shoulder; a mother seated, posture rigid, lace collar immaculate; four children arranged with careful symmetry.

Three boys in matching knickers and stiff white shirts.

And a small girl in a pale cotton dress embroidered with flowers along the hem.

Maya studied the faces first.

She always did.

Years of research had trained her to read what people could not say aloud in nineteen hundred Mississippi.

The father’s expression was composed, almost defiant, but his eyes carried restraint, as if daring the camera to betray him.

The mother’s gaze was steady, exhaustion hidden beneath discipline.

The boys were too serious for their ages—children taught early that stillness could be safety.

Then Maya’s attention dropped.

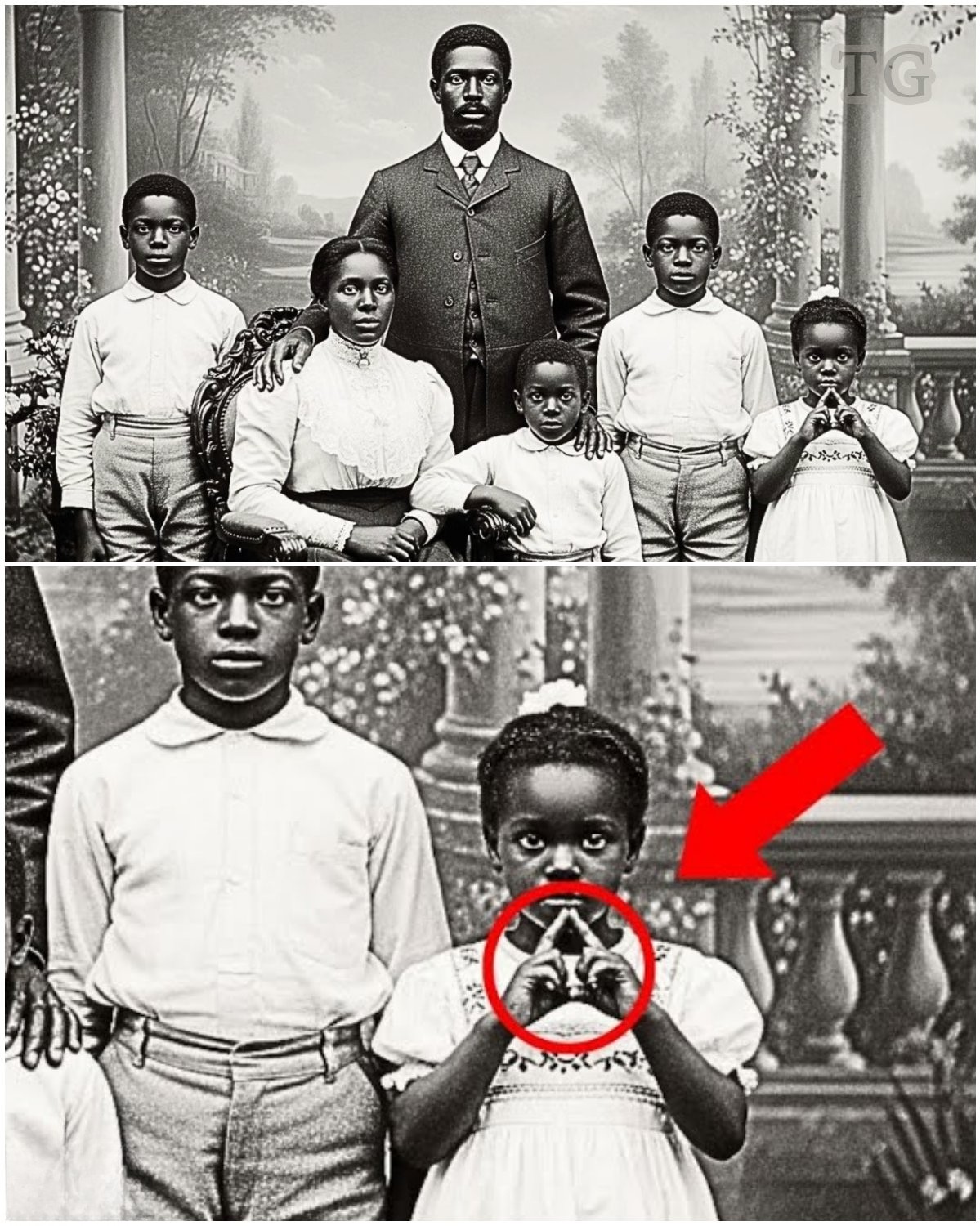

The little girl’s left hand rested against her chest.

Not loosely.

Not naturally.

Three fingers were raised.

Two crossed tightly over the thumb.

Maya froze.

She leaned closer, breath shallow.

The gesture was precise—unnervingly so.

A child that young could not accidentally form such a shape and hold it through a long exposure.

Early studio portraits demanded absolute stillness for several seconds.

Children fidgeted.

They blurred.

They ruined plates.

This child did neither.

Maya photographed the detail, zooming in until the grain of the paper dissolved into pixels.

The tension in the fingers was unmistakable.

This was not a moment captured.

It was a message delivered.

A faint unease crept in, the kind Maya recognized from past discoveries—the sensation of standing at the edge of something history had tried very hard to bury.

She checked the acquisition record.

Donated in nineteen eighty-seven from a Chicago estate.

No names.

No provenance beyond Mississippi family, circa nineteen hundred.

A dead end on paper.

But Maya had learned long ago that silence in archives was rarely accidental.

She pinned a printout of the hand to her corkboard and spent the rest of the day unable to focus on anything else.

By the third night, she hadn’t slept.

Her office filled with maps of Mississippi at the turn of the century, census tables, scholarly texts on Reconstruction’s collapse into intimidation and crackdown.

She searched for documented hand signals among enslaved communities and post-emancipation support networks.

Quilts.

Songs.

Biblical metaphors.

None matched what she saw.

On the fifth day, desperation pushed her to email Dr. Elliot Richardson, a retired historian at Howard University whose work on covert Black mutual-aid networks bordered on legend.

She attached the image without explanation.

His reply arrived two hours later.

This changes everything I thought I knew.

Call me.

Now.

Elliot’s voice trembled when Maya dialed.

“Where did you find this?”

“Smithsonian. Cataloged. Forgotten.”

A pause. Then, quietly, “The Underground Railroad didn’t end in eighteen sixty-five.”

Maya closed her notebook.

“That’s not—”

“That’s the version safe enough to teach,” Elliot interrupted.

“After Reconstruction fell apart, Black families needed protection more than ever. Freedom without protection is just exposure. The networks adapted. They never stopped.”

He hesitated, as if weighing how much to say.

“There were rumors. Hand signals taught to children. Codes that left no paper trail. But I never believed I’d see proof.”

“What does the signal mean?” Maya asked.

Elliot exhaled.

“We called it the reload signal. It meant: We are connected. We are prepared. We can help—or we need help. Children carried it because children moved unseen.”

The implication hit Maya with physical force.

The child in the photograph had been trained for a future her parents feared they might not be allowed to reach.

That night, Maya noticed something she had missed before.

On the back of the photograph, beneath decades of fading, a studio stamp emerged under magnification: Sterling & Sons Photography, Natchez, Miss.

Natchez.

She knew the city’s history too well.

Sterling & Sons had been one of the few studios in Mississippi willing to photograph Black families at the turn of the century.

Census records confirmed it operated from eighteen ninety-two to nineteen eleven.

Its founder, Marcus Sterling, was described in a nineteen twenty-eight obituary as a “respected colored businessman.” No scandals. No footnotes. But when Maya traced his son, James Sterling, the trail led north—to Chicago. The same city listed in the donation record.

James Sterling’s great-granddaughter, Vanessa Hughes, answered Maya’s email within hours.

Come see me.

Three days later, Maya sat in a South Side living room surrounded by five generations of photographs.

Vanessa, silver-haired and soft-spoken, brought out a wooden trunk scarred by age.

“My great-grandfather carried this from Mississippi,” she said.

“He never let anyone open it.”

Inside lay hundreds of glass plate negatives and three leather-bound journals.

Maya’s hands shook as she turned the pages.

Names. Dates. Notes.

Then she found it.

September fourteenth, nineteen hundred.

Coleman family.

Six portraits.

Express order.

Special arrangement.

“What does that mean?” Maya asked.

Vanessa didn’t answer immediately.

“It means they were leaving.”

The glass plate negative revealed details the paper print hid.

The child’s hand, sharper than ever.

And something else.

The mother wore a ring.

On it, a tiny symbol—three interlocking circles forming a triangle.

Maya flipped back through the journal.

Several families bore symbols in the margins.

Stars.

Lines.

Circles.

The Colemans had three interlocking circles.

Network families.

As Maya traced the Coleman name through Natchez property records, the truth sharpened.

Isaac Coleman had owned forty acres.

Land.

Independence.

In August of nineteen hundred, the region buckled under a surge of mob intimidation—families threatened, homes targeted, churches damaged, land taken through “tax” traps that weren’t really about taxes.

The photograph was taken at the height of that pressure.

By October, the Coleman property was auctioned.

By then, the family was gone.

Tracking them north took weeks.

Census records blurred into one another.

The name Coleman appeared endlessly.

Until Detroit, nineteen ten.

Isaac.

Esther.

Thomas.

Benjamin.

Samuel.

Ruth.

They had survived.

But Maya’s certainty fractured when she noticed a handwritten note in the margin: Family declined to provide prior address.

Even a decade later, they were hiding.

Maya followed Ruth’s life through fragments—school records, a marriage certificate, church rosters.

She taught Sunday school for nearly forty years at Second Baptist Church of Detroit.

A church that had once been a terminal on the original Underground Railroad.

When Maya contacted Ruth’s daughter, Grace Thompson, the past cracked open.

Grace recognized the gesture instantly.

“My mother did that once,” she whispered over the phone.

“At church. An old woman saw it and started crying.”

In Grace’s home, a small wooden box revealed what words never had: a hand-drawn travel map, a child’s dress, a Bible worn thin by years of handling.

Evidence.

But the final twist came weeks later, buried in James Sterling’s third journal.

A single entry from October of nineteen hundred.

Reload failed.

Signal compromised.

Unknown breach.

Maya stared at the page.

If the signal had been compromised… who else had been watching?

And how many families hadn’t made it?

As preparations began for a new museum exhibition, Maya couldn’t shake the feeling that the photograph wasn’t just history—it was a warning.

A reminder that some networks survive not because danger ends, but because it changes shape.

Late one night, alone in her office, Maya received an email from an address she didn’t recognize.

No subject line.

Just an attachment.

A scanned photograph.

Another family.

Another child.

Another hand, forming the same signal.

And written beneath it, in careful script:

You’re not the first to notice.

Maya leaned back in her chair, the room suddenly too quiet.

Outside, the city slept.

And somewhere, a language thought lost was still being spoken.