Inside the Fatal Flight of John F. Kennedy Jr.: A Factual Examination of the 1999 Accident

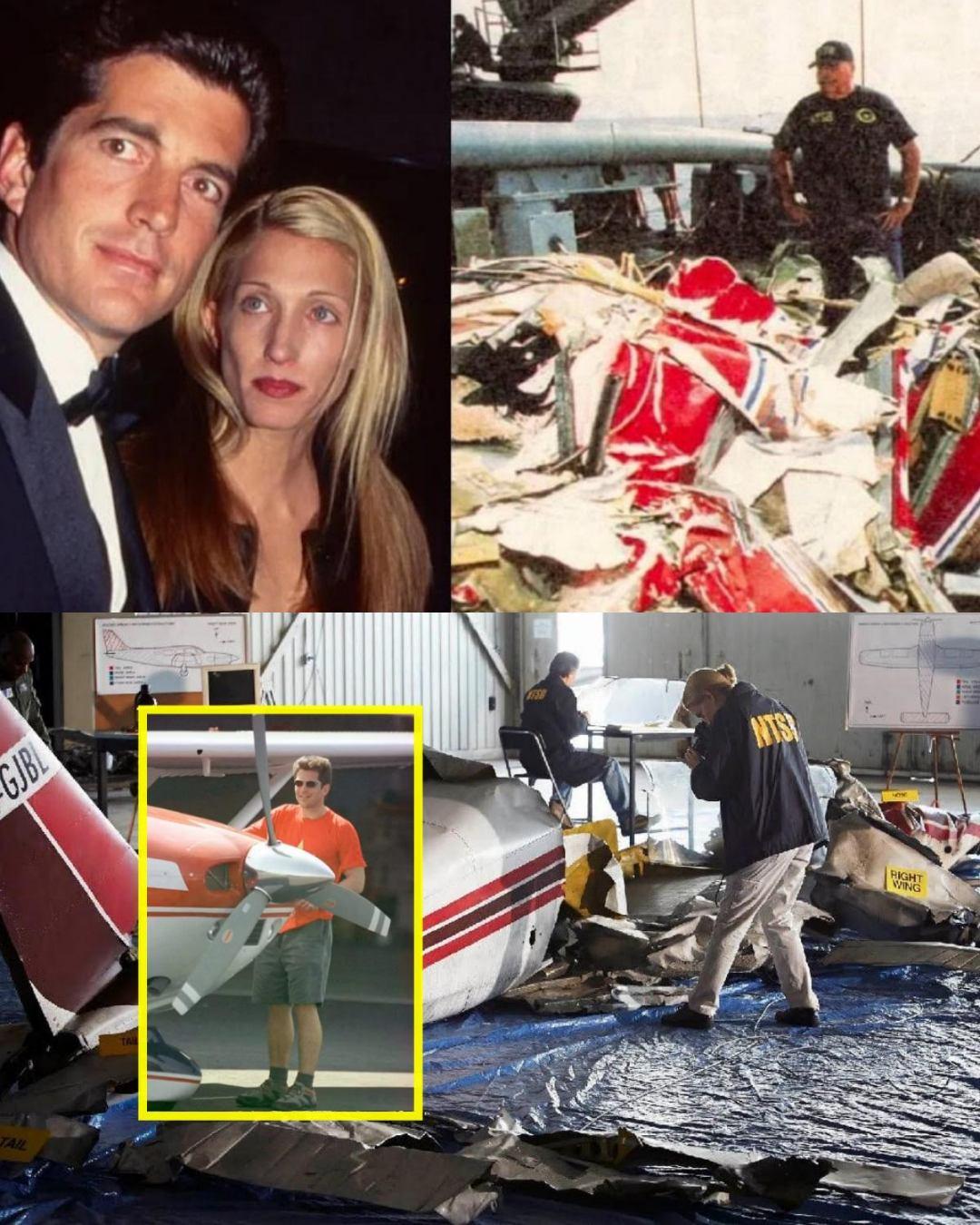

On July 16, 1999, John F. Kennedy Jr., his wife Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and her sister Lauren Bessette departed New Jersey for Martha’s Vineyard in a Piper Saratoga aircraft. It was a familiar route for Kennedy, who had flown it before. Yet the flight never reached its destination, ending instead in an accident that has remained the focus of extensive public attention and aviation analysis for more than two decades.

This article revisits the event through verified investigative findings and widely accepted aviation research, offering a clear understanding of the circumstances that led to the tragedy.

Kennedy’s Path Into Aviation

John F. Kennedy Jr. developed an interest in flying in the early 1980s. He began lessons in his early twenties, although his training at that time was sporadic. Records indicate that by the late 1980s, he had accumulated fewer than 50 hours of flight time and only a single hour of solo practice. He later paused his training for several years.

Kennedy returned to aviation in the mid-1990s with a renewed commitment. He trained in Florida, earned his private pilot certificate, and completed additional instruction over several years. By early 1999, he had logged several hundred hours and passed the FAA’s written instrument exam, though he had not yet earned an instrument rating. This meant he was permitted to fly only under visual flight rules (VFR), which require sufficient outside visibility to maintain control and orientation.

The Piper Saratoga II: Capable but Demanding

In April 1999, Kennedy purchased a Piper Saratoga II HP, a single-engine aircraft known for its speed and reliability. The airplane was equipped with an autopilot system, but one that required active monitoring—particularly in conditions involving low visibility, high workload, or deteriorating weather.

Investigators later found no evidence of mechanical malfunction. The aircraft was considered airworthy, and its systems, including the engine and control surfaces, showed no sign of failure prior to impact.

The Day of the Flight: Factors Leading to Increased Risk

While high-profile aviation accidents are often attributed to a single error or mechanical issue, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) concluded that the circumstances leading up to this flight involved a combination of human-factor challenges. Several conditions on the day of the flight increased the risk associated with a night VFR journey over water.

Recent Ankle Injury

Kennedy had fractured his ankle weeks before the trip and was still recovering. Any physical discomfort could have contributed to fatigue or distraction during a demanding night flight.

Schedule Delays

The passengers planned to leave around 6 p.m., which would have provided more daylight. However, a series of delays moved the departure to 8:38 p.m., placing the aircraft in the air shortly after sunset.

Fatigue

Kennedy had been awake many hours by the time he took off, and fatigue is known to impair judgment, slow reaction time, and reduce situational awareness in pilots.

Weather and Visibility

Although the conditions met VFR minimums, visibility was significantly reduced by haze, and the lack of moonlight made it difficult to distinguish the horizon. These conditions created what aviation experts call a “featureless environment,” where water, sky, and darkness blend into a single visual field. Such environments can lead to spatial disorientation—a recognized cause of accidents among non-instrument-rated pilots.

The Flight Path and Initial Performance

The flight departed Essex County Airport without incident. Kennedy acknowledged instructions from air traffic control, and recorded radar data shows the aircraft climbing steadily to approximately 5,500 feet. For the first portion of the trip, the aircraft maintained a stable course toward Martha’s Vineyard.

Nothing in the radar data suggests abrupt maneuvers, mechanical problems, or communication challenges during this stage.

The Descent Toward Martha’s Vineyard

Approximately 34 miles from the destination, the aircraft began its descent. Data indicate small altitude and directional variations that investigators consider typical for a non-instrument-rated pilot operating at night in marginal visibility.

However, as the aircraft moved farther from shore, visual cues diminished. The horizon was not discernible, and lights from land were minimal. Without clear visual references, pilots must rely on instruments—something pilots without full instrument training may struggle to do effectively.

Spatial Disorientation: A Well-Documented Hazard

The NTSB concluded that the accident was consistent with spatial disorientation, a condition that occurs when a pilot cannot accurately interpret the aircraft’s attitude, altitude, or motion. When external visual references disappear, the body’s internal sense of motion becomes unreliable.

The most common outcome is an unintentional banked turn. If uncorrected, this can evolve into a tightening descending spiral. The pilot may not realize the aircraft is banking or descending because the sensations of motion can feel normal, leading the pilot to trust physical perception instead of instruments.

In Kennedy’s case, radar data indicated a series of changes in altitude and heading that escalated into a rapid descending turn. The descent rate increased beyond what could be recovered in time, resulting in the aircraft impacting the Atlantic Ocean.

The Final Minutes: Verified Radar Reconstruction

The NTSB’s radar analysis shows:

-

The aircraft began a descent toward Martha’s Vineyard.

-

Minor heading changes became more pronounced as visibility decreased.

-

The descent rate increased, ultimately surpassing 4,000 feet per minute.

-

No radio distress call was made, and no attempt to climb out of the descent is evident.

The absence of a distress call is consistent with spatial disorientation, as affected pilots often do not realize an emergency is unfolding until recovery is no longer possible.

Alternative Theories and Investigative Results

Over the years, speculation has circulated widely regarding mechanical failure or external interference. The NTSB’s investigation examined these possibilities and found no evidence supporting mechanical problems, structural failure, or sabotage. The findings align with a well-documented pattern of accidents involving non-instrument-rated pilots flying at night over water during marginal visibility.

Impact on Aviation Safety and Training

The accident prompted renewed discussion in the aviation community about training standards, pilot decision-making, and night-flying risks. Flight instructors frequently reference the case as an illustration of:

-

The challenges of night VFR over featureless terrain

-

The importance of instrument proficiency

-

The risks of combining fatigue, stress, and limited visibility

It has since been incorporated into safety seminars and training curricula as a reminder of how quickly spatial disorientation can occur.

Remembering the Passengers

John F. Kennedy Jr., Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and Lauren Bessette were well-known public figures whose lives ended unexpectedly. The accident had a profound effect on the public and on aviation communities. Tributes focused on their contributions, their professional accomplishments, and the broader legacy of the Kennedy family.

Conclusion

The flight that claimed the lives of John F. Kennedy Jr., Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and Lauren Bessette was not the result of a mechanical failure or extraordinary event. Instead, the NTSB determined that a combination of environmental conditions, night flying limitations, and human factors contributed to spatial disorientation, leading to loss of control.

By examining the accident through established aviation principles and official records, the event stands as a significant case study in flight safety. It underscores the importance of instrument training, careful assessment of weather and visibility, and the need for pilots to recognize how quickly disorientation can occur when visual cues disappear.

Understanding these factors not only provides clarity about the tragedy but also reinforces lessons that continue to shape aviation safety today.