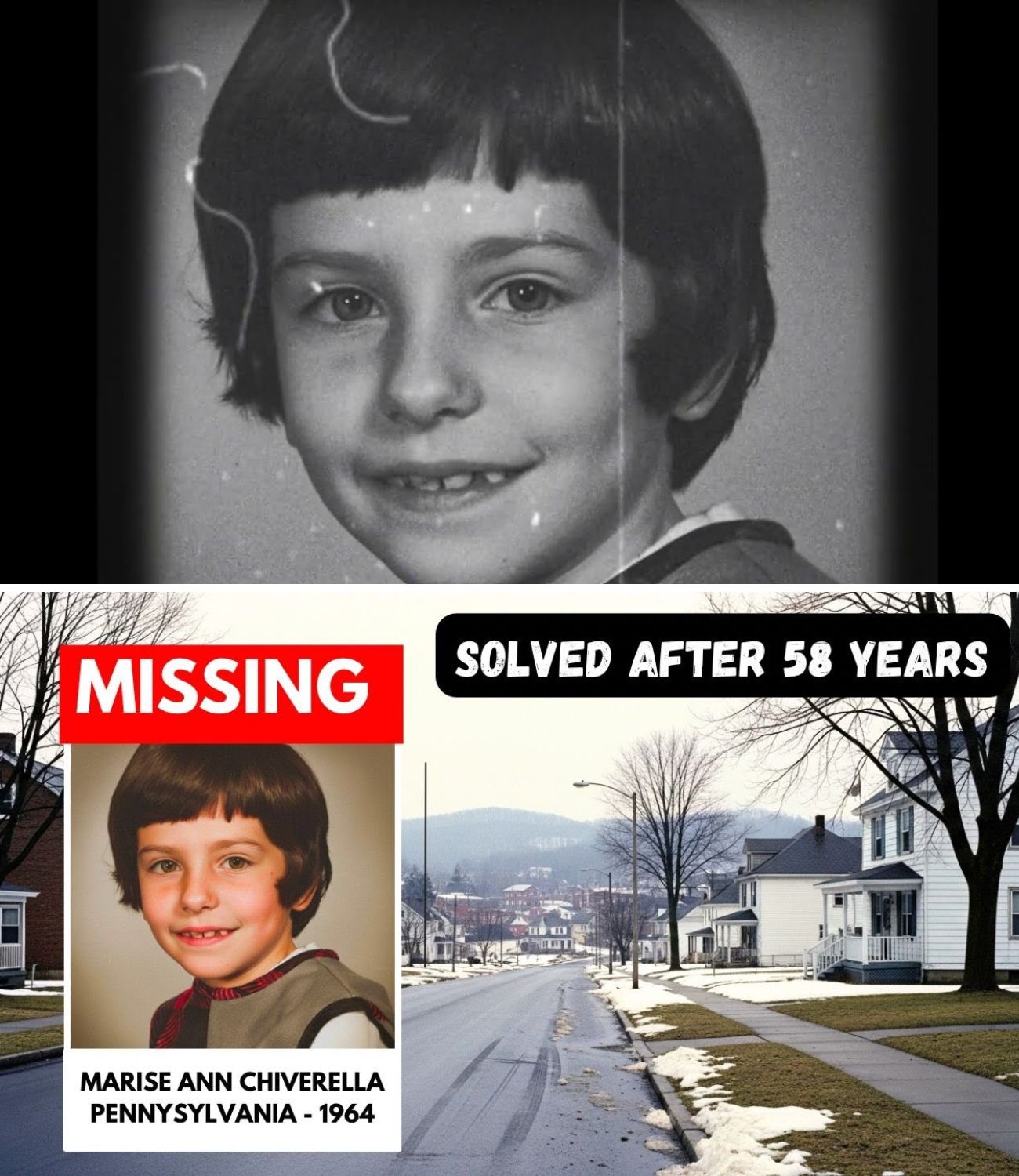

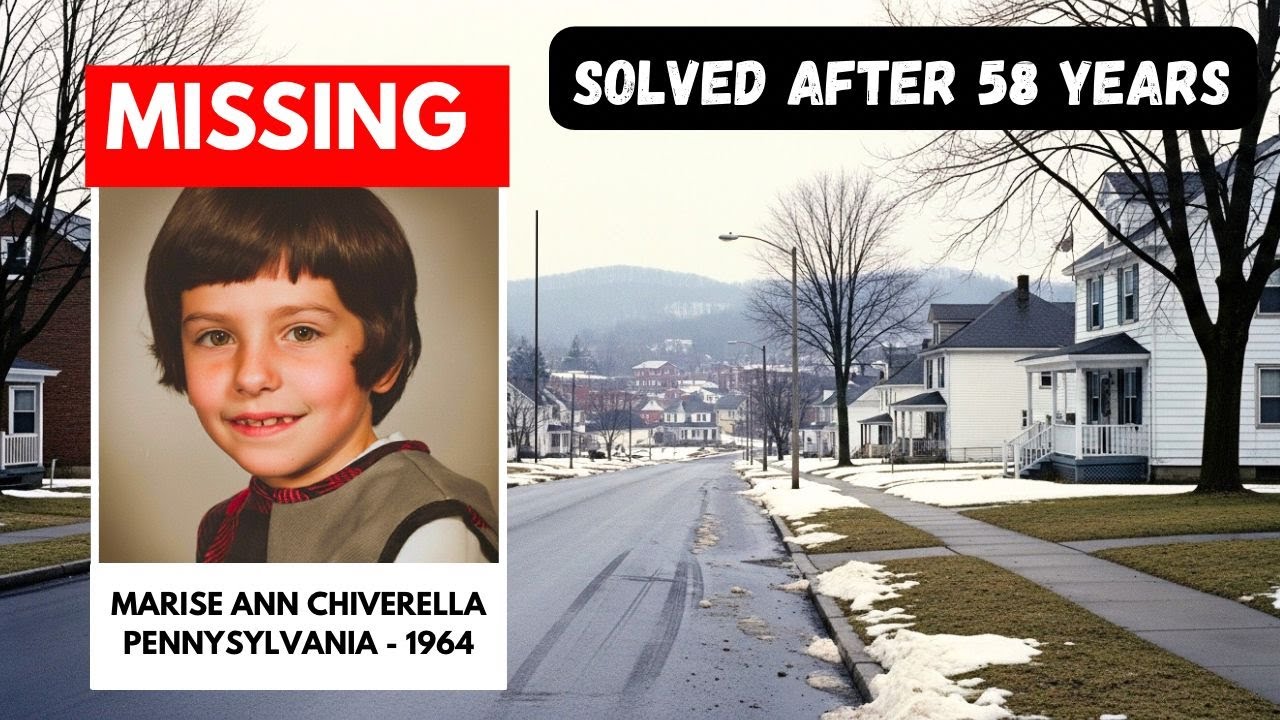

It was a moment nearly six decades in the making. In February 2022, at a Pennsylvania State Police press conference, Corporal Mark Baron stepped to the podium and announced that one of the state’s longest-running unsolved cases had finally been resolved. His voice carried the weight of thousands of hours of work, of a promise kept, and of a community that had lived under a shadow for generations. The case was the 1964 killing of 9-year-old Marise Ann Chiverella from Hazleton, Pennsylvania, and its resolution would become known as one of the oldest cold cases in American history to be solved through modern DNA techniques.

For the town of Hazleton, this case was never just another file. It was a defining moment that changed how families lived and how children were protected. For the Chiverella family, it was a lifetime of unanswered questions, a constant space at the table for a daughter and sister who never had the chance to grow up. And for investigators, it was a test of patience, perseverance, and faith in evolving science.

The Morning That Changed a Town

In March 1964, Hazleton was a close-knit coal town where neighbors knew one another and children often walked to school without concern. On the cold morning of March 18, 9-year-old Marise was especially excited. The following day, her parochial school would celebrate the Feast of St. Joseph, and she had carefully chosen canned goods from her father’s small grocery store to donate as part of the celebration.

Marise asked for permission to walk to school alone that day so she could arrive early, drop off her contributions, and attend morning mass. It was a short walk, and her parents agreed. Neighbors later recalled seeing her making her way along the route, determined to reach school despite the wind and low temperatures.

That was the last time her family and community saw her alive.

When Marise did not return home as expected and her teacher reported that she had been absent all morning, her family immediately began searching. The police were quickly notified, and the community mobilized. What began as a hopeful search soon turned into a heartbreaking discovery at an abandoned coal site several miles away. There, officers found Marise’s body and some of her belongings.

The precise investigative details of that day were painful and disturbing, and over time, law enforcement has focused on describing them with care and respect. What is clear is that a serious and violent crime had been committed against a child, and Hazleton’s sense of safety was permanently altered. Parents became more cautious, children were no longer allowed to walk alone as freely, and the case etched itself into the town’s collective memory.

Decades of Unanswered Questions

In the months that followed, the Pennsylvania State Police conducted one of the most extensive investigations in the state’s history. Detectives worked long hours, pursued every lead, and interviewed hundreds of people. Over time, the case file grew to more than 6,000 pages, with contributions from more than 230 troopers and investigators across multiple generations.

Despite the effort, the case remained unsolved. Some individuals were questioned and, for a time, considered persons of interest, but no charges were ever brought. Tips faded, witnesses aged, and the physical evidence available in the 1960s offered limited options for analysis.

For the Chiverella family, life moved forward but never quite healed. Marise’s siblings grew up, started families, and built their own lives, yet they carried their sister’s memory with them everywhere. Their parents, Mary and Carmen, held onto hope that one day there would be an answer. Family members later shared that at many holiday dinners and family gatherings, their mother ended her prayers with the same request: that the person responsible would one day be identified and justice would be done.

The case was never closed. It remained an open investigation on the books of the Pennsylvania State Police, reviewed repeatedly as new techniques and technologies emerged. Each new detective assigned to the file inherited not just documents and evidence, but the weight of a family’s decades-long hope.

A Breakthrough in the DNA Era

The first meaningful scientific break came in 2007, more than 40 years after the crime. Advances in forensic DNA analysis allowed experts at the state police laboratory to extract a usable DNA profile from evidence preserved since 1964. The careful work of the original investigators, who had methodically stored key items, suddenly became critically important.

That DNA profile was compared against the national criminal database, but no match was found. The individual responsible had never been entered into the system. The profile, however, gave investigators something new: a stable genetic identifier that could potentially be used in the future as forensic science evolved.

That evolution arrived in the form of forensic genetic genealogy. Starting around the mid-2010s, investigators across the United States began using publicly accessible genealogy databases, with appropriate safeguards and consent procedures, to identify unknown suspects by linking crime scene DNA to distant relatives. This method had already played a major role in solving other long-standing cases.

In the Chiverella investigation, Pennsylvania authorities partnered with specialists in genetic genealogy to explore this avenue. The crime scene DNA profile was uploaded to a public genealogy database, where it was compared with profiles voluntarily submitted by individuals searching for family connections. Eventually, investigators found a distant relative who shared a small portion of DNA with the unknown suspect, providing an initial link in a very large and complex family tree.

The Student Genealogist Who Helped Connect the Dots

Around this time, an 18-year-old college student and enthusiastic genealogist, Eric Schubert, contacted the Pennsylvania State Police after reading about the case. He offered to help with the genealogical research, drawing on years of experience tracing family histories as a hobby and in collaboration with law enforcement on other cases.

After vetting his background and abilities, investigators decided to work with him. From his dorm room, Schubert devoted many hours each week to expanding and narrowing the family tree built from that single distant DNA match. With guidance from the police and additional voluntary DNA samples from relatives, he helped map out potential ancestral lines.

The work was painstaking. From a distant match that might reflect a connection many generations back, genealogical research had to move step by step through historical records, birth and death certificates, and family branches spread across time and geography. Over months of quiet, methodical effort, the possible field of candidates grew smaller.

Eventually, attention centered on one man who had lived in Hazleton at the time of the crime: James Paul Forte.

Giving a Name to a Long-Standing Shadow

Forte’s name had never appeared in the original case files. He had not been interviewed or identified as a suspect in 1964. Yet the genealogical research suggested that he was strongly linked to the crime scene DNA through shared family ancestry.

Further review of historical records revealed that Forte lived within walking distance of the Chiverella home during the time of the crime. Later in life, he was also known to have been involved in other serious incidents, though at the time those did not result in lengthy prison terms.

Because Forte had passed away in 1980, investigators could not question him or bring a case to trial. To confirm their suspicions, they obtained legal authorization to exhume his remains. A sample taken from his remains was submitted for testing.

In early 2022, the laboratory results came back: the DNA from Forte’s remains matched the profile taken from the evidence preserved from 1964. Statistically, the chance of such a match occurring by coincidence was extraordinarily small. After 58 years, investigators were able to state with confidence that they had identified the individual responsible.

Justice and Closure, Even Without a Trial

When state police officials and members of the Chiverella family gathered for the February 2022 press conference, the moment was filled with both relief and sadness. There would never be a courtroom trial. Forte could not be questioned, confronted, or sentenced. Yet the truth, supported by science and years of investigative work, had finally been brought to light.

Marise’s siblings spoke about their sister, their parents, and the decades they had spent living with unanswered questions. They emphasized that their family had not sought revenge, but clarity and justice. Knowing the identity of the person responsible gave them a measure of peace, even as they continued to feel the absence of a sister whose life was cut short.

For the Pennsylvania State Police, the resolution of the case represented a powerful example of investigative persistence combined with modern science. Generations of detectives had refused to let the file gather dust. The careful preservation of evidence in 1964, the development of DNA technology in the 2000s, the emergence of forensic genetic genealogy, and the contributions of outside specialists, including a college student determined to help, all played a role.

More broadly, the Chiverella case illustrates how advances in forensic science can offer hope in other long-unsolved cases. While not every cold case will have preserved evidence suitable for DNA analysis, and not every investigation will lead to such a clear resolution, the combination of technology, collaboration, and commitment can bring answers that once seemed out of reach.

For Hazleton, the case is now part of its history rather than its unresolved present. For the Chiverella family, it is a reminder that even after many decades, the truth can emerge. And for investigators across the country, it stands as encouragement to continue pursuing difficult cases—because sometimes, justice simply takes time.